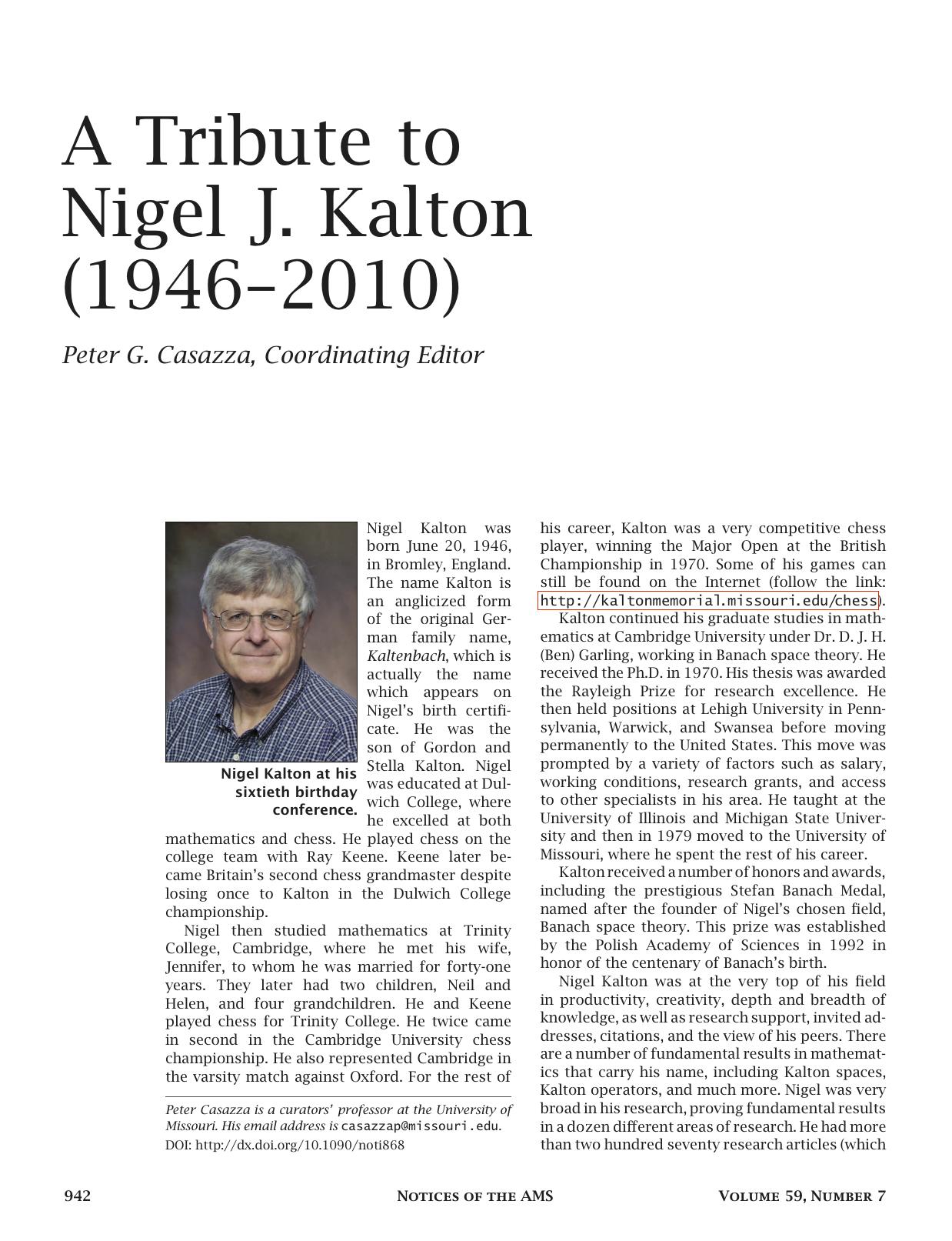

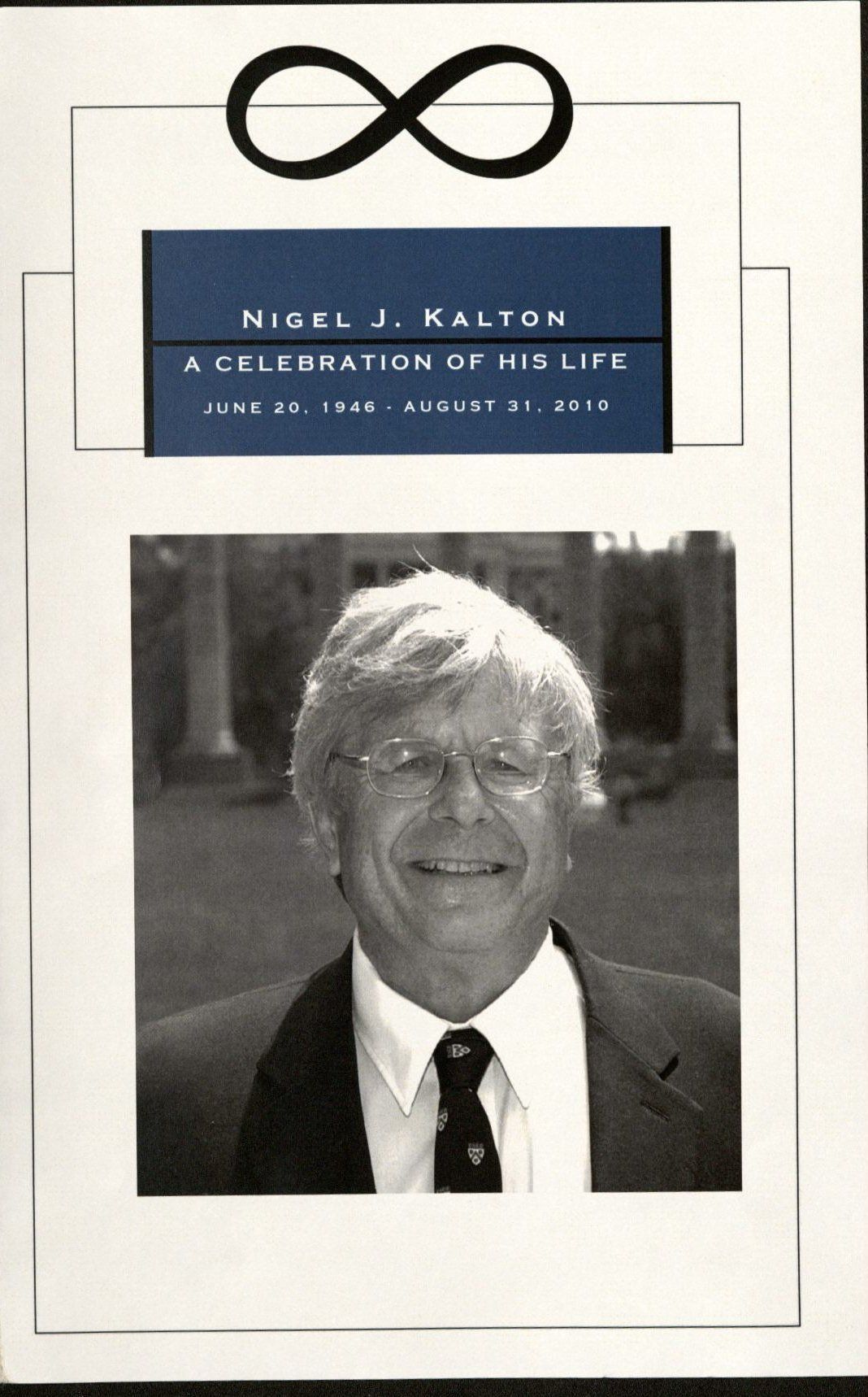

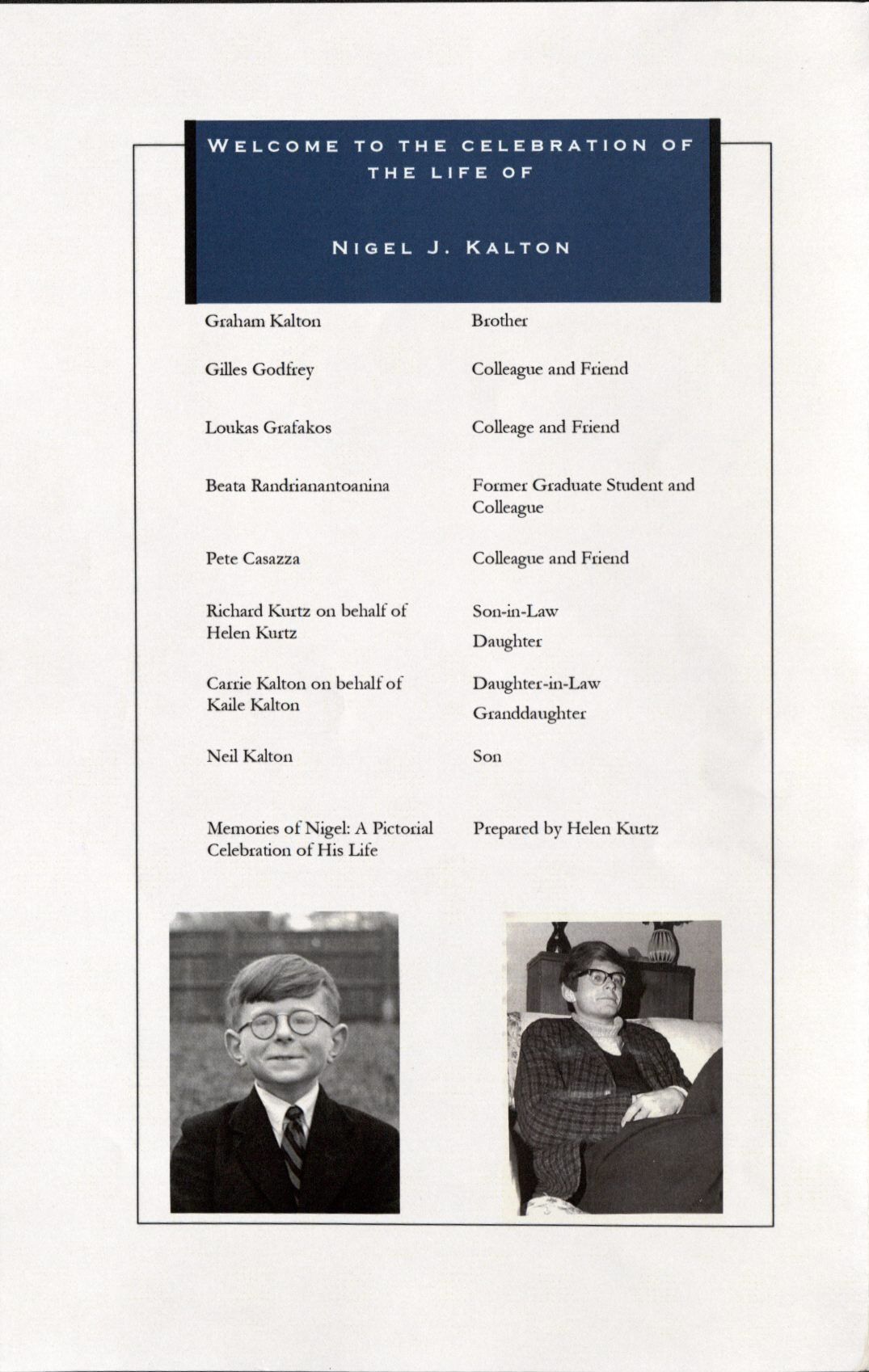

Home | CV & Publications | Banach Medal | Collaborators | On Kalton's Work | Remembering Nigel | Chess | Picture Gallery | Obituaries

Remembering Nigel

Nigel was my PhD adviser. I can hardly express how important he has been for me. Through my time in Missouri, it was not just his mathematical vision and taste that I bene ted from but, maybe more importantly, his human qualities, which made my PhD years such a fantastic experience. Strangely, I have felt closer to him after that time, as I got deeper into mathematics and started to grasp a bit better the role he played in Analysis. Things he said keep coming back to me, and I keep finding myself reading some of his papers at times when I believe that I am working on totally different topics.

Although I very much wish I could discuss these things with him now, drinking a nice glass of wine somewhere on the planet, I still feel his presence through the stunning web of ideas and results he left us. Over the years, I have come to realise just how little I understood of what Nigel told me, and I am sure that I will soon look back at my current understanding, and feel stupid once again. Here I would like to recall one discussion, on a non-mathematical topic, that I now understand in a completely di erent way than I did at the time, back in 2002.

Drinking beer in a pub in Atlanta, and feeling a bit tipsy, we came to the subject of how to live a mathematician's life. Nigel made a statement that I found shocking at the time: he said that the basic way to go was to pick five people working on similar topics at a similar level, and compete with them. This fitted well with Nigel's image as an athlete-like competitor, and clashed with my cooperative vision of science, and my general disdain for the sort of competition found in sport. I thought, back then, that it was a bit sad that such a great mathematician would have this kind of motivation, but that, in the end, what mattered was the beautiful results he produced, not what drove him. But I feel now that my initial understanding of Nigel's competitiveness was very naive.

There are many silly ways to be competitive as a mathematician. Some people look at number of papers, citations, or journals reputations. Some people spend their energy publicising their fields or results, and choose topics that optimise their visibility. But Nigel was not this sort of competitor. He wanted results that answer important questions, proofs that show the nature of the results, theories that demonstrate the unity of Analysis and Mathematics in general, and he did not settle until he got exactly that, and wrote the paper that needed to be written. This form of competitiveness has nothing to do with running a millisecond faster than someone else or publishing 1% more papers. Maybe it can be found in the very top athletes, maybe it is what drives artists, maybe it is competition with oneself or with Nature itself, and you can also call your five competitors your five inspirational colleagues. I am too young and naive to know this, but, whatever it is, there is something beautiful about it, and that is how I remember Nigel.

Pierre Portal, Australian National University and Universite Lille 1 (on leave), June 2011.

October 1st, 2010

The last time Nigel visited Spain was in June, as a plenary speaker of an international Functional Analysis conference held in Valencia. He had flown from the US on purpose, and since he was returning right after the conference, he had decided to stay jet‐lagged for the duration of the congress. So, apart from the brilliant talks that he delivered, Nigel was up when others were in bed and vice versa, which prevented us from hanging out with him after the talks. With a tired look he confessed to us that he was planning a change of strategy and instead of attending so many conferences around the world, he would now go for longer invited visits. And we felt very lucky because Nigel loved Spain!! Almost as much as Spanish mathematicians loved Nigel.

For the last 25 years we have benefited from his wisdom and generosity. He visited us often and always welcomed us in Columbia. The development of Analysis in Spain owes Nigel Kalton a great deal. With his passing away not only do we lose one of our main sources of inspiration but an invaluable friend.

Fernando Albiac, Jesús Bastero, Teresa Bermúdez, Julio Bernués, Félix Cabello, Pilar Cembranos, Julio Flores, Francisco Hernández, Camino Leránoz, and Pedro Tradacete on behalf of many mathematicians of Spain

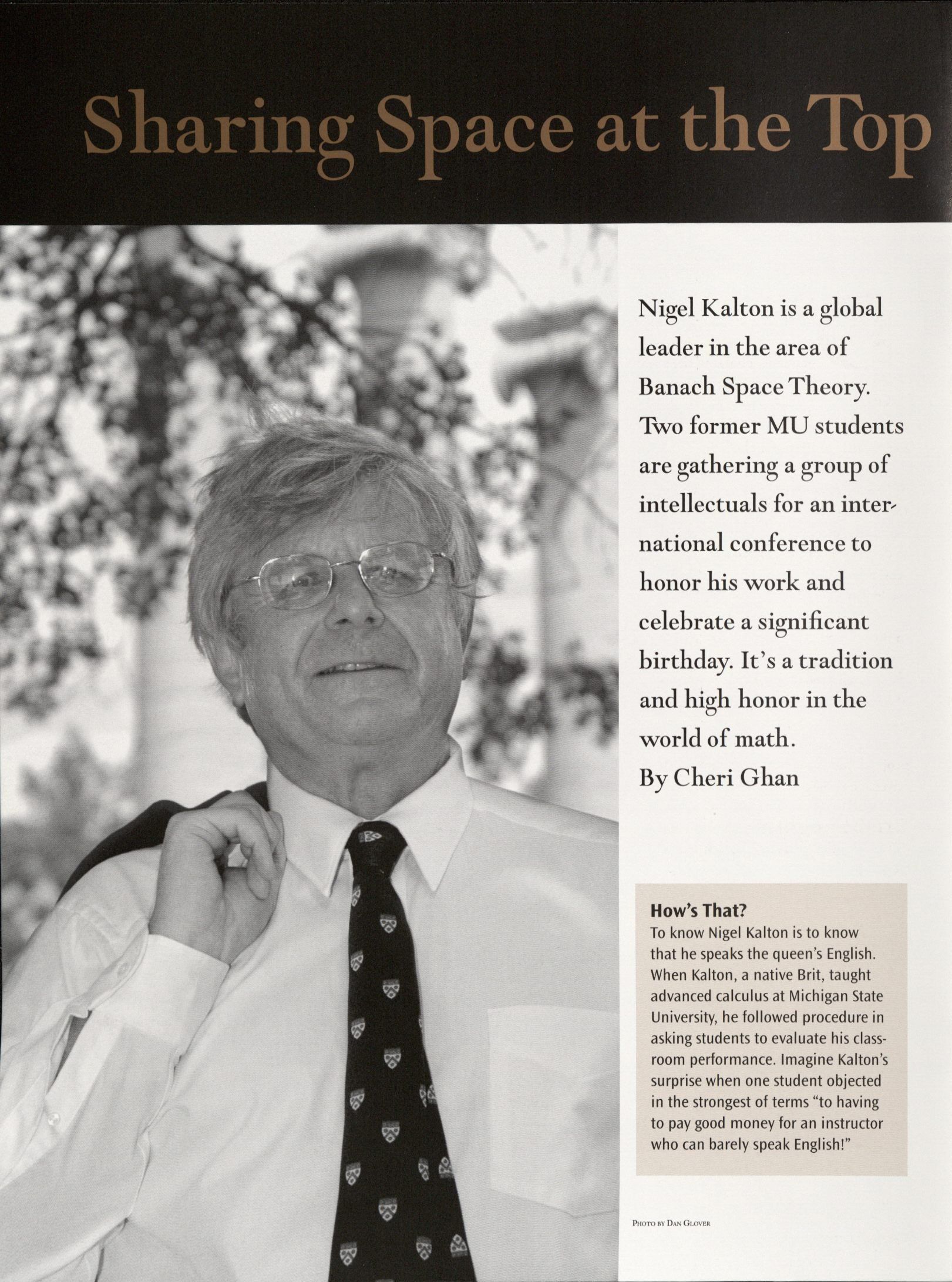

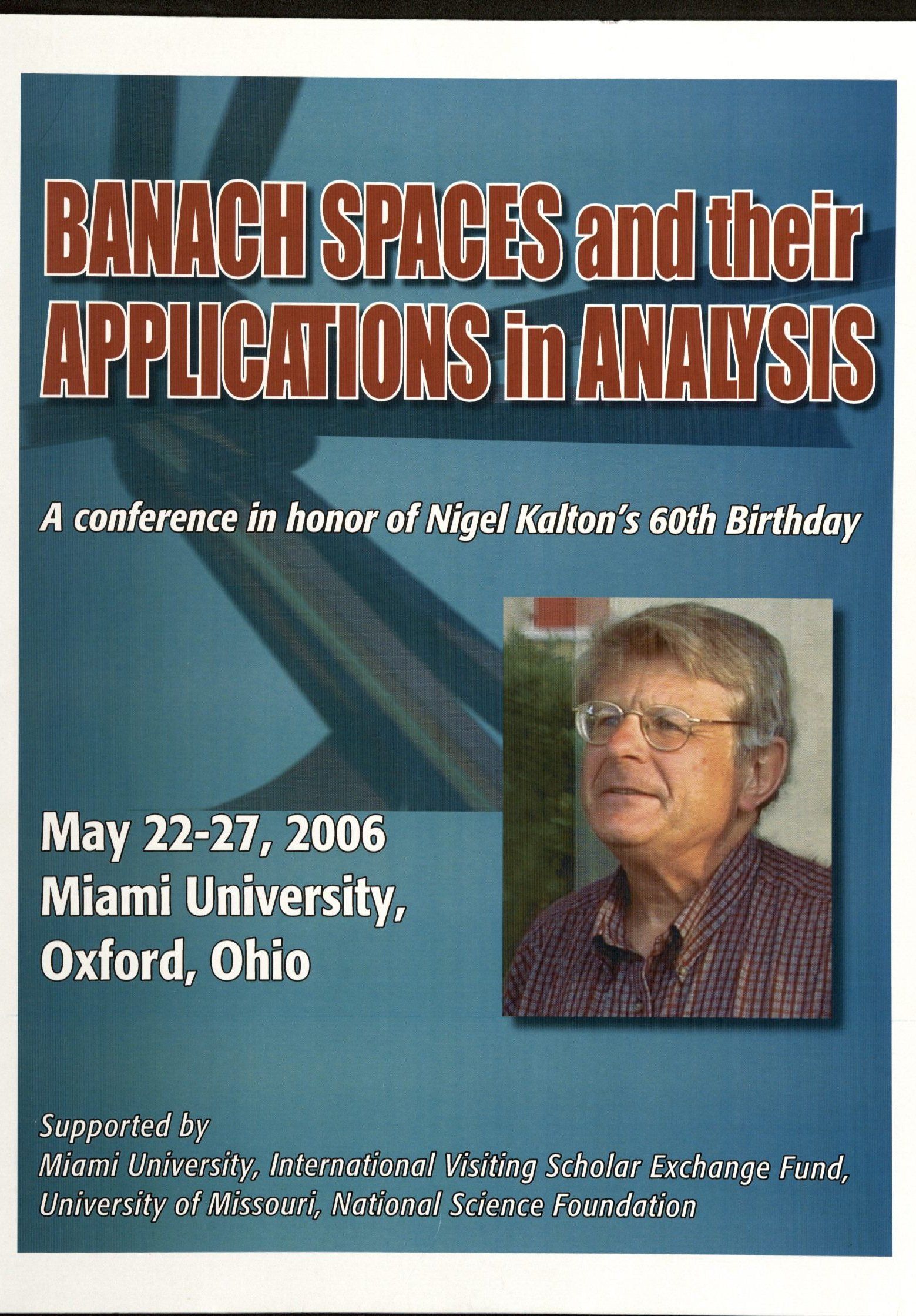

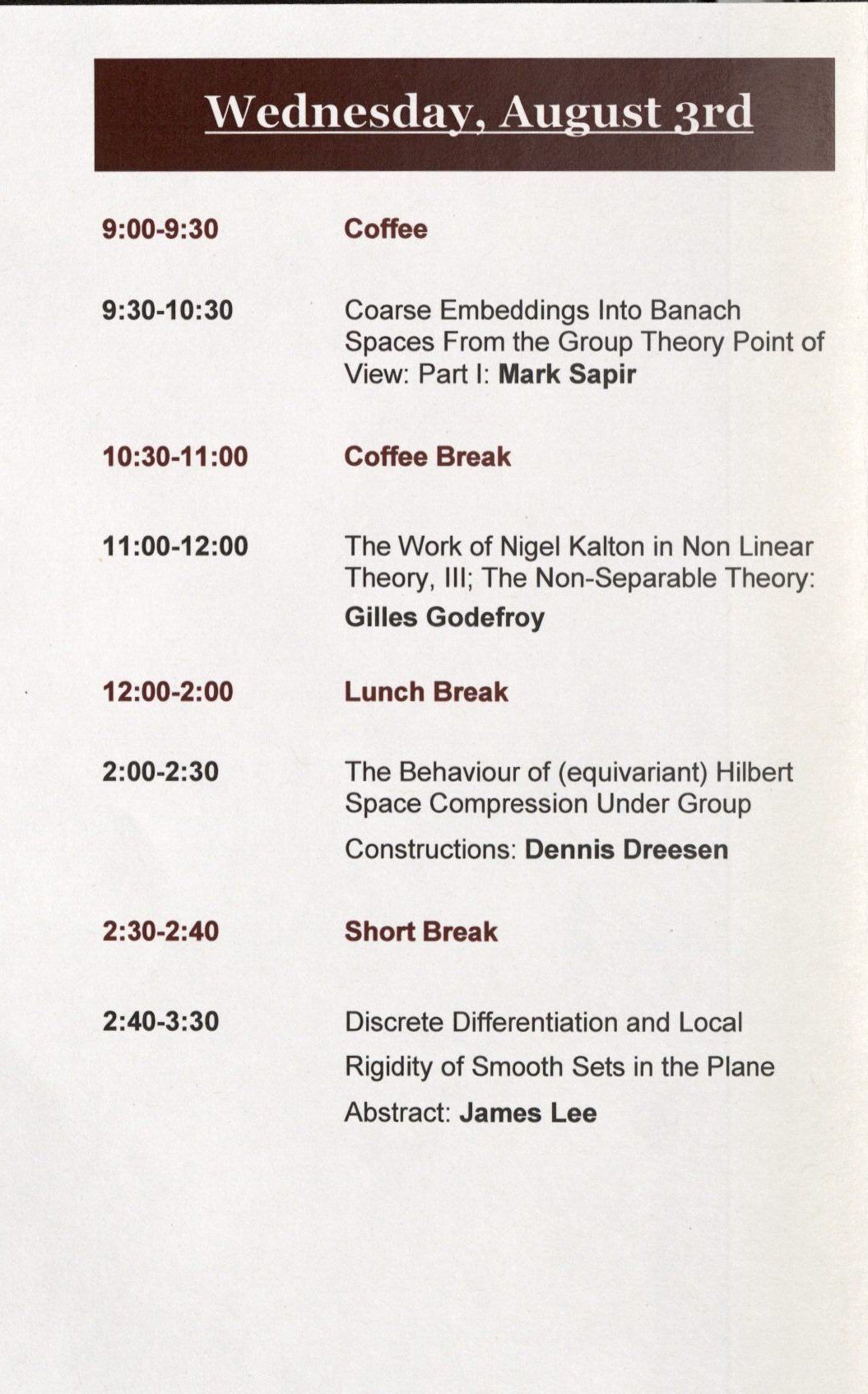

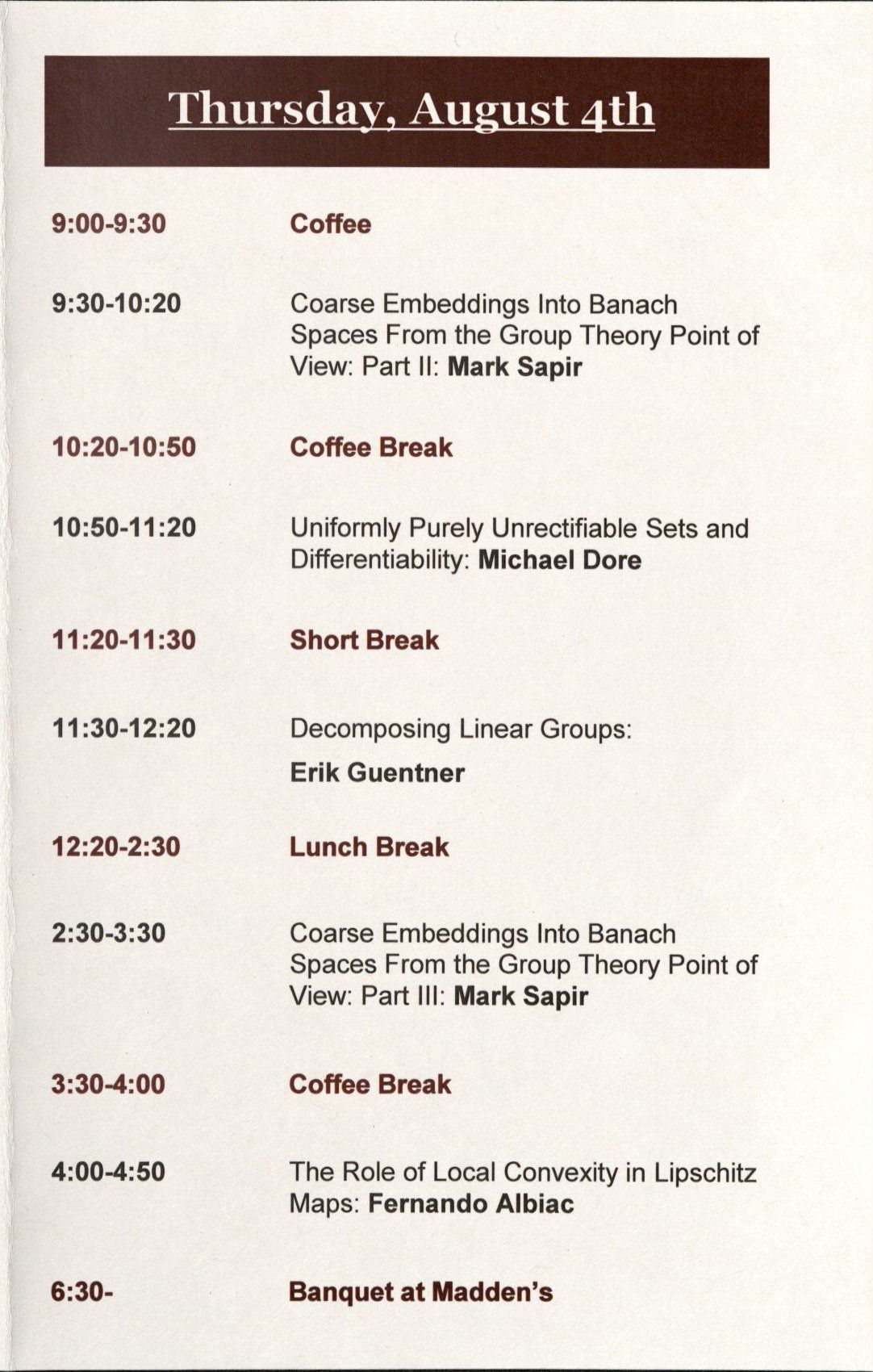

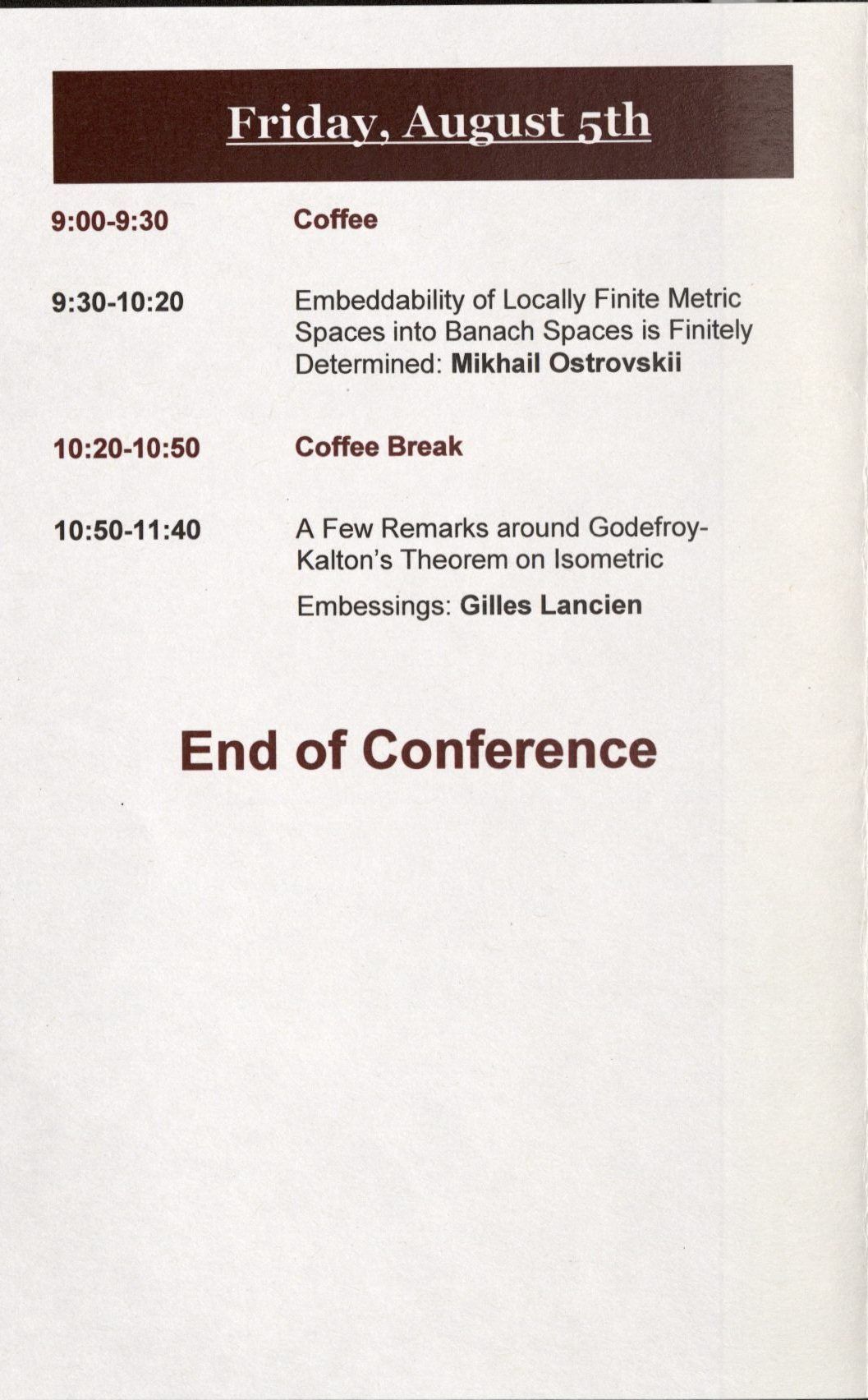

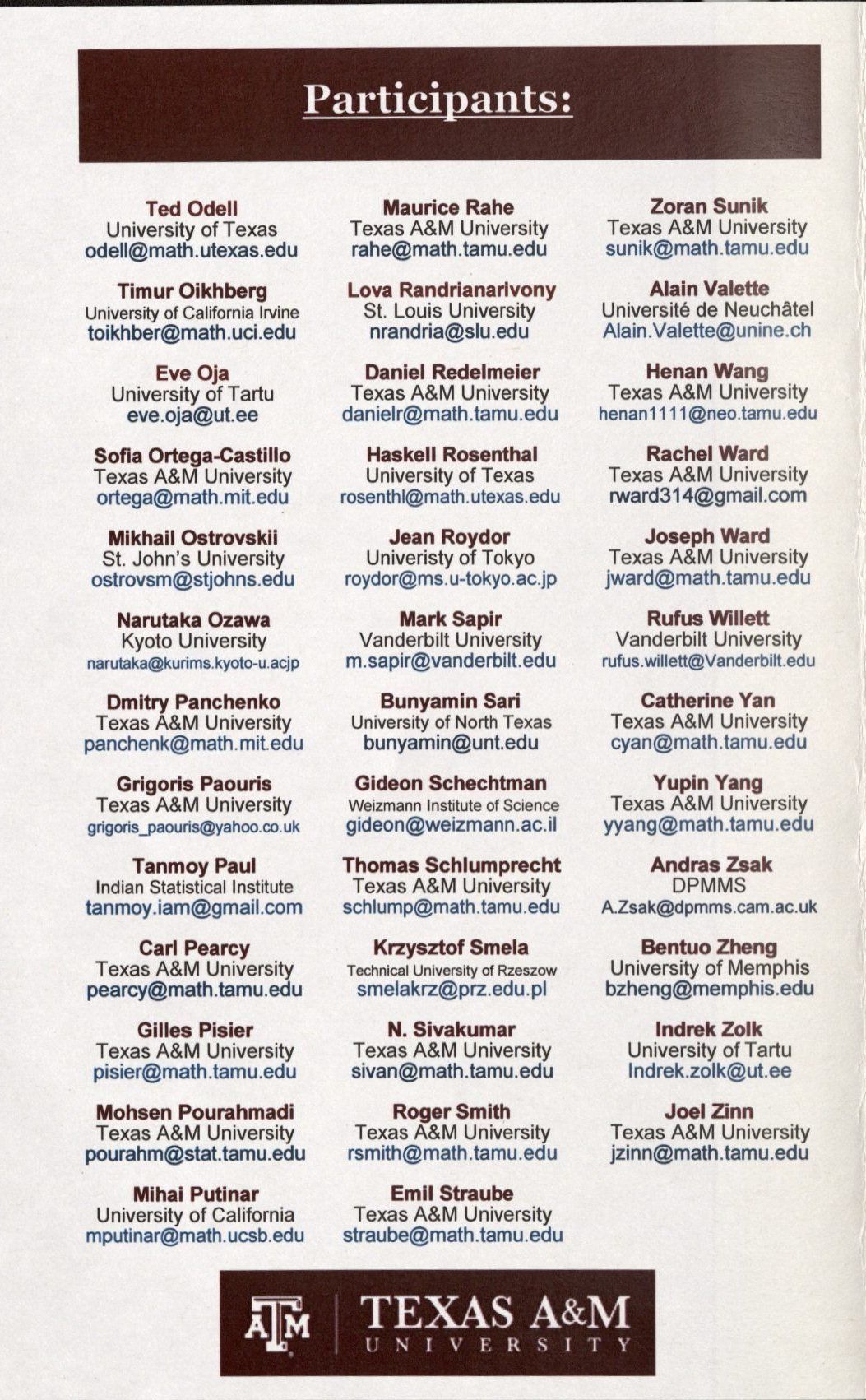

Birthday Conference: Banach Spaces and their Applications in Analysis

List of Abstracts

Proceedings

Workshop Abstracts

The following video was taken at Garth Dales’ Presentation at the international conference, Espaces de Banach et applications à l’analyse, January 12-16, 2015, Centre International de Rencontres Mathématiques (CIRM), Luminy, Marseille, France.

Works best with Google Chrome.

http://programme-scientifique.weebly.com/1127.html